Teach the

free man how to praise. What is there to say about the writers who settle in

and become part of your everyday life, co-habiting in ear and mind? Most of the

time, as a critic and teacher, the texts that set me writing are the ones I can’t

fully assent to, books that lodge themselves in my memory in ways that can feel

stuck or misplaced; texts to worry to and with. Other writers, other poems,

sink so deeply in the mind I reach for them all the time, but wouldn’t know how

to say why. Auden, Bishop, Glover: their lines, learnt in adolescence, I’ve

detached from poems and worked in to personal vocabulary.

Seamus Heaney was one of these writers for me. His poems are a continuing

source of joy and sustenance, to be sure, but many of them feel so familiar –

and so right – the brilliance of

their achievement threatens to end up obscured. Isn’t that how I’ve always described

such things, even if “that last / gh”

isn’t mine at all? There hasn’t been a week, in the sixteen years since I first

discovered him in sixth form, I haven’t

read or remembered or gone back to a Heaney poem, all the time thinking that somewhere

or other his own voice has been going on and new works were still to come. A companion,

and part of an introduction to poetry, as with the names evoked in Auden’s ‘Thanksgiving.’

The first Heaney I bought, the inscription reminds me, was his New Selected Poems on my seventeenth

birthday. ‘The squat pen’ and the showily terse equivalence of writing and ‘digging’

in the early poems were what drew me in, that gorgeously physical imagery – of peat

and field, a ‘straining rump’ labouring ‘among the flowerbeds’ – and those

terse full rhymes feeling like a kind of anti-poetry, an assertion of the place

of labour and community and commitment against abstraction. History was there,

too, and resistance: ‘And in August the barley grew up out of the grave.’ The

words were what they talked about.

How my adolescent reading combined this ‘phenomenalisation

of language’ with Heaney’s supererogatory word choices and reach in

vocabulary I can’t remember; I suspect I skimmed over the more thrawn lines in

search of further sensuous particulars. There were plenty of those. The poems

sustain that kind of naive reading – and Heaney, in his critical writing

allowed himself the occasional anti-Theory jibe – but only to let you settle in

and then ask from you more. These are poems that, eventually, teach pleasure in

dictionaries, and I’m grateful for that.

The Spirit

Level was a gift, later that year, fraught with the usual teenage baggage of

unequal, unrequited exchange, and still means more to me, I imagine, than it

ever did to the giver, if only in a kind of residually self-pitying and maudlin

bitter way: ‘A deep mistaken chivalry, old friend. / At this stage only foul

play cleans the slate.’ (The ‘Invocation’ to MacDiarmid’s ‘far-out, blathering genius’

would have meant nothing to me then; ‘endure / At an embraced distance’ feels

right now.)

Some lines I memorised on first encounter for their sound and feel as if I’m

only now learning how to grow into. All those very Irish punning terms for good

conduct (‘govern your tongue!’) helped, and Heaney’s clear-sighted risk-taking

in registering particular kinds of sadness without giving in self-indulgence or

‘expressiveness’:

When I went

to the gents

There was a

skewered heart

And a

legend of love. Let me

Sleep on

your breast to the airport.

Living in Tokyo, and travelling a split shift between teaching jobs, I’d

often stop at the Oshima Book Store, picking up cheap copies of Heaney second

hand. Station Island; Wintering Out; Seeing Things; Sweeney Astray

– I re-discovered these either down the road in Ochanomizu, reading Heaney

while drinking vodka and eating borscht at Russia Tei, or on the train home.

‘They

seem hundreds of years away,’ those days, but re-reading the lines now brings

an almost physical sense of the joy and personal help the encounters brought.

Coping with the poems’ intellect and range and formal loveliness better now,

and not in such a hurry to force them into adolescent patterns, there were new

delights.

The refusals of Heaney’s poems from the 1970s, the way the poems turn

eloquently in on themselves, marking false phrases off in quotation and

worrying through, feel to me like his best work. ‘Whatever you say say nothing’

still astonishes:

Is there

life before death? That’s chalked up

In

Ballymurphy. Competence with pain,

Coherent

miseries, a bite and sup,

We hug our

little destiny again.

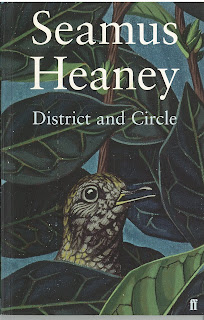

Poems make good companions. I bought District

and Circle and Human Chain around

about this time last year, in Dunedin for

the funeral of a dearly-loved friend. They were good, helpful choices:

It was your

first leave,

A stranger

arrived

In a house

with no upstairs,

But heaven

enough

To be going

on with.

The whole of you a-patter, ‘alive and ticking like an electric fence’: that’s

the Heaney sensation, and I wish there could be more of it still. But this is

no bad word-hoard at all.

I drink to

you

in smoke-mirled,

blue-black,

polished

sloes, bitter

and

dependable.